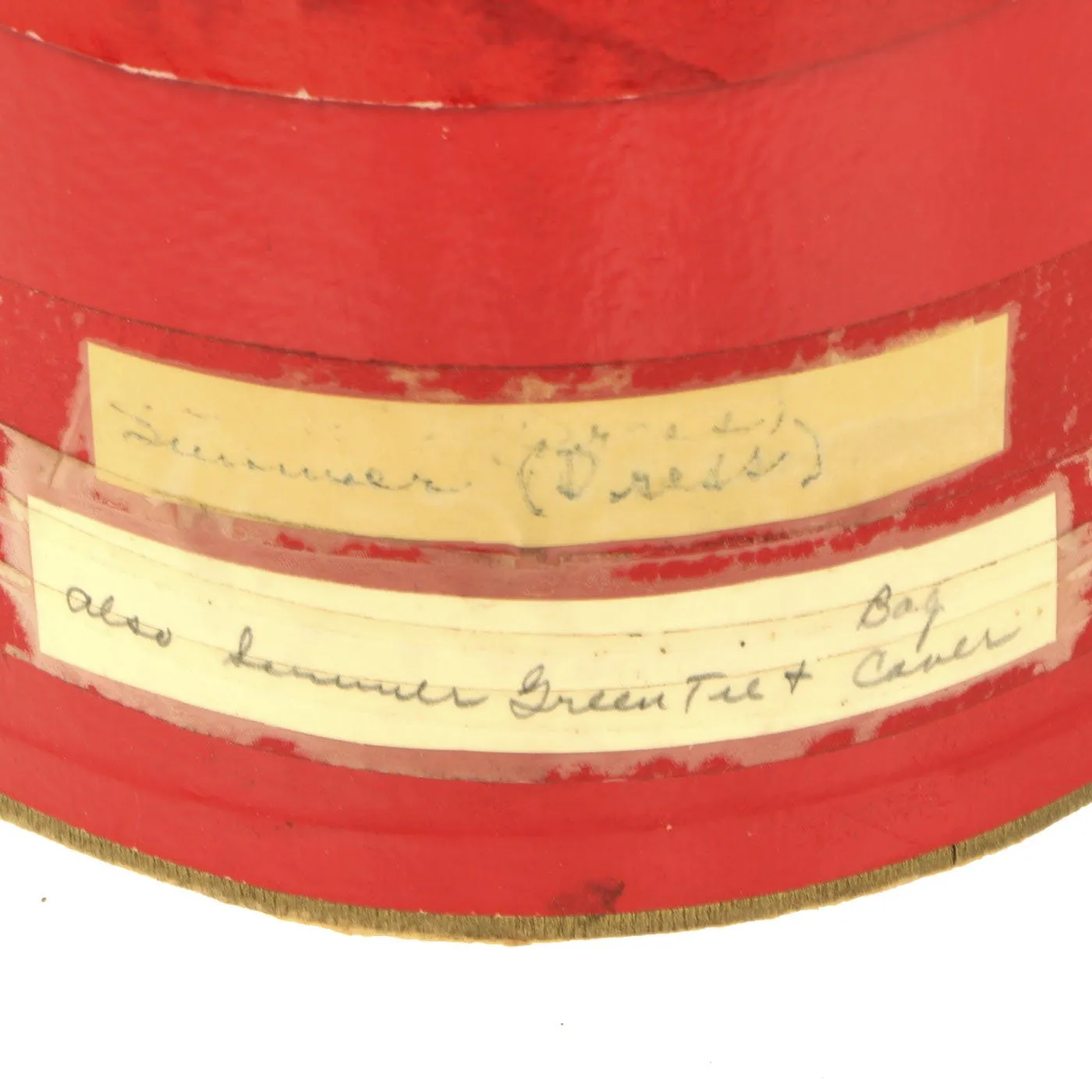

Original Item: Only One Available. This is an extremely rare excellent condition United States Marine Corps USMC women's officer cap dating from the very end or just after World War Two. It is constructed of navy blue wool and features bullion embroidered gilt oak leaves to the visor, large gilt and silver screw back Eagle Globe Anchor hat badge insignia, yellow corded chinstrap, and two gilt EGA buttons. The interior is lined in rayon. Size is approximately 6 1/2 US. Also included is the original scarlet hat box marked AMROSE, NEW YORK.

Some stories sound too contrived to be true, yet are repeated too often to be dismissed as mere folklore. One such tale was rescued and restored to its rightful place in history when Mary Eddy Furman confirmed that, yes, the portrait of Archibald Henderson, 5th Commandant of the Marine Corps, crashed from the wall to the buffet the evening that Major General Commandant Thomas Holcomb announced his decision to recruit women into the Corps. Mrs. Furman, then a child, was a dinner guest at a bon voyage dinner party given for her father, Colonel William A. Eddy, and the Commandant's son, Marine Lieutenant Franklin Holcomb, on 12 October 1942 when the Commandant was asked, "General Holcomb, what do you think about having women in the Marine Corps?" Before he could reply, the painting of Archibald Henderson fell.

We can only surmise how Archibald Henderson would have reacted to the notion of using women to relieve male Marines "for essential combat duty." On the other hand, General Holcomb's opposition was well-known. He, as many other Marines, was not happy at the prospect. But, in the fall of 1942, faced with the losses suffered during the campaign for Guadalcanal — and potential future losses in upcoming operations — added to mounting manpower demands, he ran out of options.

With 143,388 Marines on board and tasked by the Joint Chiefs of Staff to add 164,273 within a year, the Marine Corps had already lowered its recruiting standards and raised the age ceiling to 36. At the same time, President Roosevelt's plan to impose a draft threatened the elite image earned by the selective, hard-fighting, disciplined Marines, and so, the Commandant did what he had to do. In furtherance of the war effort, he recommended that as many women as possible should be used in non combatant billets.

The idea was unpopular, but neither original nor unprecedented; women were already serving with the Army and in the Navy and Coast Guard Reserves. In fact, during World War I, 300 "Marinettes" had freed male Marines from their desks and typewriters at Headquarters, Marine Corps, to go to France.

Periodically, between World War I and World War II, prodded by people like Army Chief of Staff General George C. Marshall and Congresswoman Edith Nourse Rogers, military and elected leaders gave fleeting thought to the idea of a womens corps. Marshall knew that General John J. Pershing had specifically asked for, but not received, uniformed female troops. Rogers, a Red Cross volunteer in France in 1917, was angry that women who had been wounded and disabled during the war were not entitled to health care or veterans' benefits. She promised that ". . . women would not again serve with the Army without the protection the men got."

Yet, until 1941, not many people took the available studies seriously and even advocates could not agree on whether the women should be enlisted directly into the military or be kept separate, in an auxiliary, where they would work as hostesses, librarians, canteen workers, cooks, waitresses, chauffeurs, messengers, and strolling minstrels.

Congresswoman Rogers eventually compromised and settled for a small auxiliary and in May 1941 she introduced H.R. 4906, a bill to establish the Women's Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC) to make available ". . . to the national defense the knowledge, skill, and special training of the women of the nation." The legislators argued and stalled. Even the brazen Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor was not enough to move them to pass the bill until 15 May 1942.

Unfortunately, the notion was doomed from the start and the WAAC, an auxiliary of women who were neither military nor civilian, ultimately was reorganized and converted to full military status as the Women's Army Corps (WAC) in late summer 1943. Meanwhile the Navy watched the unraveling of the WAAC very closely as it struggled with its own version of a plan for women.

Some say there were naval officers who preferred to enlist ducks, dogs, or monkeys to solve the manpower shortage, but the decision was made at the highest level to use women and furthermore, recognizing the fate of the failed WAAC, the women would be "in" the Navy. With sideline help from Mrs. Franklin D. Roosevelt, the Navy bill, Public Law 689, was signed on 30 July 1942, establishing the Navy Women's Reserve (WAVES). The same law authorized a Marine Corps Women's Reserve (MCWR), but the Marines weren't ready to concede just yet. In the meantime, the Coast Guard formed a women's reserve, the SPARS.

Bowing to increasing pressure from the Congress, the Secretary of the Navy, and the public, the M-1 section of Plans and Policies at Headquarters, Marine Corps, proposed a women's reserve to be placed in the Division of Reserve of the then-Adjutant-Inspector's Department. The Commandant, in the absence of reasonable alternatives, sent the recommendation to Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox, and, in the end, the matter was finally settled for the Corps on 7 November 1942 when President Franklin D. Roosevelt gave his assent.

Early Planning

On 5 November, the Commandant wrote to the commanding officers of all Marine posts and procurement districts to prepare them for the forthcoming MCWR and to ask for their best estimates of the number of Women Reservists (WRs) needed to replace officers and men as office clerks, radiomen, drivers, mechanics, messmen, commissary clerks, etc. He made clear that, within the next year the manpower shortage would be such that it would be incumbent on all concerned with the national welfare to replace men by women in all possible positions.

Armed with the responses, planners tried to project how many women possessing the required skills would be enlisted and put to work immediately, and how many would need special training in such fields as paymaster, quartermaster, and communicator. Based on their calculations, quotas were established for recruiting and training classes were scheduled.

Early estimates called for an initial target of 500 officers and 6,000 enlisted women within four months, and a total of 1,000 officers and 18,000 enlisted women by June 1944. The plan for rank and grade distribution followed the same pattern as the men's with only minor differences. For officers there would be one major and 35 captains, with the balance of the remaining commissioned officers being first and second lieutenants.

The highest rank, fixed by Public Law 689, permitted one lieutenant commander in the Women's Reserve of the U.S. Naval Reserve, whose counterpart in the Marine Corps would be a major. Eventually, the law was amended so that the senior woman in the Navy and Coast Guard was promoted to captain and in the Marine Corps to colonel.

The public, anticipating a catchy nickname for women Marines much like the WACS, WAVES, and SPARS, bombarded Headquarters with suggestions: MARS, Femarines, WAMS, Dainty Devil-Dogs, Glamarines, Women's Leather-neck Aides, and even Sub-Marines. Surprisingly, considering his open opposition to using women at all, General Holcomb adamantly ruled out all cute names and acronyms and when answering yet another reporter on the subject, stated his views very forcefully in an article in the 27 March 1944 issue of Life magazine: "They are Marines. They don't have a nickname and they don't need one. They get their basic training in a Marine atmosphere at a Marine post. They inherit the traditions of Marines. They are Marines"

Marine women of World War II were enormously proud to belong to the only military service that shared its name with them and, actually, insisted upon it. It happened that, in practice, they were most often called Women Reservists, informally shortened to WRs. When referred to as women Marines, or Marine women, the "w" was not capitalized as it was later, after the passage of the Armed Forces Integration Act of 1948, the law that gave women regular status in the military. Then, Women Marines were best known as WMs. In fact, women would have to wait 30 years before the gender designator would be dropped and they at last would be simply Marines.

The First WRs

The decision to organize the Women's Reserve in the Division of Reserve was natural because the division was already responsible for recruiting all reserve personnel. Up to this point it had nothing to do with training, but now, it inherited all matters pertaining to the Women's Reserve, including training, uniforming, and administering. An organization created within the Division, the Women's Reserve Section, Officer Procurement Division, was staffed to handle the new activity. It very capably accomplished its first mission, the selection of a suitable woman for the position of Director of the MCWR when the eminently qualified Mrs. Ruth Cheney Streeter was commissioned a major and sworn in by the Secretary of the Navy on 29 January 1943.

Major Streeter was not, however, the first woman on active duty in the World War II Marine Corps. A few weeks earlier, Mrs. Anne A. Lentz, a civilian clothing expert who had helped design the uniforms for the embryonic MCWR, was quietly commissioned with the rank of captain. She had come to Marine Headquarters on a 30-day assignment from the WAAC and stayed.

By all accounts, the selection of Mrs. Streeter to head the MCWR was inspired. It fell to this woman who had never before held a paying job, to facilitate recruiting, training, administration, and uniforming of the new Women's Reserve.

Mrs. Streeter, 47, president of her class at Byrn Mawr despite completing only two years of college, wife of a prominent lawyer and businessman, mother of four including three sons in service and a 15-year-old daughter, and actively involved for 20 years in New Jersey health and welfare work, was selected from a field of 12 outstanding women recommended by Dean Virginia C. Gildersleeve of Barnard College, Columbia University. Dean Gildersleeve chaired the Advisory Educational Council which had earlier recommended to the Navy the selection of Lieutenant Commander Mildred McAfee, Director of the WAVES.

Colonel Littleton W. T. Waller, Jr., Director of Reserve, and his assistant, Major C. Brewster Rhoads, travelled across the country to interview all candidates personally, and discreet inquiries also were made about the nominees. The Commandant firmly believed the success of the MCWR would depend largely on the character and capabilities of its director. Mrs. Streeter must have seemed an obvious choice. She was confident, spirited, fiercely patriotic, and high-principled. Discussing the interview in later life, she said:

As nearly as I can make out, General Holcomb said, "If I've got to have women, I've got to have somebody in charge in whom I've got complete confidence." So he called on General Waller. General Waller said, "If I've got to be responsible for the women, I've got to have some body in whom I have complete confidence." And he called on Major Rhoads. So then the two of them came out to see me.

Having passed muster with both Colonel Waller and Major Rhoads, Mrs. Streeter was scheduled for an interview with General Holcomb. In the course of the first meeting, he asked repeatedly whether she knew any Marines. Dismayed, and convinced she would be disqualified because she did not know the right people, she answered honestly that she knew no Marines. In fact, this was exactly what the Commandant wanted to hear because he worried that if she had high-ranking friends in the Corps, she might circumvent the chain of command when she couldn't get her way. After the interview, Colonel Waller said he thought it went well, but the appointment still had to be approved by the Secretary of the Navy. That was good news for Mrs. Streeter since Secretary Knox was a close friend of her mother and her in-laws, and her husband had been the Secretary's personal counsel.

Throughout her long life, Ruth Streeter remained a devoted Marine, but the Corps had not been her first choice. After the fall of France in 1940, Mrs. Streeter believed the United States would be drawn into war. In interviews she spoke of German submarines sinking American ships a mile or two off the New Jersey shore, in plain sight of Atlantic City. So, fully intending to be part of the war effort, she learned to fly, earned a commercial pilot's license, and eventually, bought her own small plane. In the summer of 1941 Streeter joined the Civil Air Patrol, and although her plane was used to fly missions aimed at keeping the enemy subs down, to her enormous frustration, she was relegated to the position of adjutant, organizing schedules and doing ". . . all the dirty work."

In later years, retired Colonel Streeter reminisced that British women were flying planes in England early in the war and she expected American women to be organized to ferry planes to Europe. When, at last, the quasi-military Women Air Service Pilots (WASPs) was formed under the leadership of the legendary aviatrix, Jackie Cochran, Mrs. Streeter was 47 years old, 12 years beyond the age limit. Nevertheless, she tried to enlist four times and was rejected four times before she asked to meet Jackie Cochran personally, and then she was rejected the fifth time.

In January 1943, before the public knew about the Marine Corps plan to enlist women, Mrs. Streeter inquired about service in the WAVES. She asked about flying in the Navy but was told she could be a ground instructor. She declined and a month later found herself in Washington, the first director of the MCWR.

After Major Streeter and Captain Lentz were on board, six additional women were recruited for positions considered critical to the success of the Women's Reserve. They were handpicked because of their special abilities, civilian training and experience, and then, with neither military training nor indoctrination, they were commissioned and assigned as follows: Women's Reserve representative for public relations, First Lieutenant E. Louise Stewart; Women's Reserve representative for training program, Captain Charlotte D. Gower; Women's Reserve representative for classification and detail, Captain Cornelia D. T. Williams; Women's Reserve representative for West Coast activities, Captain Lillian O'Malley Daly (who had been a Marinette in World War I and personal secretary to the Commandants from that time); Women's Reserve representative for recruit depot, Captain Katherine A. Towle; and Assistant to the Director, MCWR, Captain Helen C. O'Neill.

The somewhat dubious distinction of being last to take women had its benefits. The missteps and problems of the WAACs, WAVES, and SPARS were duly noted and carefully avoided by the Marines, but more significantly, the other services were generous in sharing advice and resources. Right from the beginning, the Navy was a full partner in getting the fledgling MCWR off to a good start.

There was widespread skepticism about whether men could properly select female applicants, so women were sought immediately for recruiting duty. The Navy sounded a call among WAVE officer candidates and 19 volunteers were selected for transfer and assigned to Marine procurement offices where, still dressed in their Navy uniforms, they set to work recruiting the first Marine women.

By agreement between the Navy Bureau of Personnel and Headquarters, Marine Corps, and to avoid competition in the recruiting of women for either naval service, Naval procurement offices were used by Marine procurement sections. Women interested in joining the WAVES or the Marines went to one office to enlist and receive physical examinations. In time, however, the Marine Corps developed its own network of recruiting offices. The official announcement finally came on Saturday, 13 February 1943, and women enthusiastically answered the call to "Be a Marine . . . Free a Man to Fight!" Although enlistments were scheduled to begin on the following Monday, the record shows that at least one woman, Lucille E. McClarren of Nemacolin, Pennsylvania, signed up earlier, on 13 February.

Women who aspired to serve as a WR had to meet rather stringent qualifications which prescribed not only their age, education, and state of health, but their marital status as well. At the start, the eligibility requirements were similar for both officers and enlisted women: United States citizenship; not married to a Marine; either single or married but with no children under 18; height not less than 60 inches; weight not less than 95 pounds; good vision and teeth.

For enlisted or "general service," as it was called, the age limits were from 20 to 35, and an applicant was required to have at least two years of high school. For officer candidates, requirements were the same as for WAVES and SPARS: age from 20 to 49; either a college graduate, or a combination of two years of college and two years of work experience.

In time, regulations were relaxed so that the wives of enlisted Marines were allowed to join, and enlisted women could marry after boot camp. Black women were not specifically barred from the segregated Marine Corps, but on the other hand, they were not knowingly enlisted. While it is rumored that several black women "passed" as white and served in the MCWR, none have been recorded. Officially, the first black women Marines, Annie E. Graham and Ann E. Lamb, arrived at Parris Island for boot training on 10 September 1949.

Early recruiting was so hectic that in some instances, women were sworn in and put directly to work in the procurement offices, delaying military training until later. American women were determined to do their part even if it meant defying the objections of parents, brothers, and boyfriends who tried to keep them from joining up.

Marian Bauer's parents were so shaken at her decision to enlist that they refused to see her off. But then there were the lucky ones like Jane Taylor, who remembers the wise advice from her father, a World War I sailor, "Don't ever complain to me. You're doing this of your own free will. You weren't drafted or forced. Now, go — learn, travel, and do your job to the best of your ability." Zetta Little, the daughter of Salvation Army officers, joined because, ". . . someone waved a flag and said my brother would come home from the war sooner if I did."

The Marines were serious about the weight limits and just as underweight male enlistees have always done, underweight women devoured bananas washed down with water to bring their weight up to the required 95 pounds. Audrey Bennington, after being rejected by a Navy doctor because she was underweight, left the induction center to gorge herself, and when she returned, the corpsman turned accomplice, looked away as she climbed on the scale clutching her fur coat and shoes. An equally accommodating corpsman rested his foot on the scale and wrote down 95 pounds when diminutive Danelia Wedge was weighed the second time. "Wedgie" got as far as Camp Lejeune but was afraid her military career was over when a doctor asked what had caused her to lose so much weight since enlistment. He accepted her quick response, 'Well, sir, long train rides don't agree with me."

Throughout the war the minimum age, set by law, remained unchanged even though it was sometimes difficult to defend. After all, some teenagers argued, 18-year-old girls were able to enlist in World War I, and even some 17-year-olds joined with their parents' consent. Others wondered why 18-year-old boys could be sent to combat, yet 18-year-old girls could not serve at all.

While some parents fought to keep their girls home, others asked special consideration for daughters who were too young to enlist. One of the most poignant letters came from a World War I holder of the Distinguished Service Cross who wrote to the Commandant in January 1943, even before news of the Women's Reserve was announced:

I know this is no time to reminisce, but I do want to bring this to your attention. I am the Marine from 96th Company, Sixth Regiment, who was with Lieutenant [Clifton B.] Cates and a few other Marines that captured Bouresches, France, and I turned over the first German prisoner and machine gun to you that our battalion captured on the night of 6 June 1918. I have a big request to ask . . . . As I have no sons to give to the Marines, I would be more than happy if you . . . would recommend my daughter to the newly-formed Marines Women Reserve Corps. While I appreciate that her age may be a little young, she will be 18 this June . . . I feel sure she could fit into your program . . . surely this is not too much for a D.S.C. ex-Marine to ask of you . . . .

Recruiting for the MCWR was almost too successful and one procurement officer, cautioning that the number of applicants so far exceeded the quotas that he feared a backlash of ill will, suggested that publicity be curtailed. Within one month of MCWR existence, while Marine forces regrouped after the campaign for Guadalcanal, and prepared for the move to New Georgia and the advance up the Solomons chain, Colonel Waller reported: "The women of the country have responded in just the manner we expected . . . . Thousands of women have volunteered to serve in the Women's Reserve and from them we have already selected more than 1,000 for the enlisted ranks and over 100 as officers."

Naturally, each service wanted to recruit the very best candidates, and the women directors, joined in a singleness of purpose, set aside inter-Service rivalry to get the job done. Typically, the four leaders, Major Streeter; Major Oveta Culp Hobby, WAAC and WAC; Lieutenant Commander Mildred H. McAfee, WAVES; and Lieutenant Commander Dorothy C. Stratton, SPARS, ironed out their differences on recruiting women from the war industries, civil service, and agriculture, and submit ted a recommendation to the Joint Army-Navy Personnel Board which eventually became an all-Service policy.

Women working in war industries were discouraged from enlisting, but some were persistent and in the end were required to go to the local office of the United States Employment Service for approval. Civil Service employees needed a written release "without prejudice" from their agency and when a reluctant employer released the employee "with prejudice," none of the Armed Services would consider her application for 90 days. Marines went a step further and barred their own civilian women employees who enlisted from working in their original jobs even if classified to a similar military occupational specialty.

Almost immediately, Major Streeter and the public relations officer, Lieutenant Stewart, toured the United States, speaking at many gatherings such as women's clubs and Chambers of Commerce, to explain the purpose of the MCWR and to win public support. A more subtle but equally important reason for the tour and indeed for having a Director of Women's Reserve at all, according to Colonel Streeter, ". . . was because the parents were not going to let their little darlings go in among all these wolves unless they thought that somebody was keeping a motherly eye on them."

Families had good reason to be apprehensive; the early months were difficult for the Women Reservists. Of all the problems, ranging from barracks obviously designed only for male occupancy to the scarcity of uniforms, the most trying were the stares and jeers of the men which in the words of Colonel Katherine A. Towle, second Director of the MCWR, ". . . somehow had to be brazened out."

From the start, the directors of the WACS, WAVES, SPARS, and MCWR focused their energy on the war effort, but it was difficult not to be distracted by the change in attitude of the fickle public whose early enthusiasm for women in uniform gave way to a nasty, demeaning smear campaign that started as a whisper and grew to a roar. The WAAC took the brunt of the abuse and never really recovered. It was so bad that some suggested it might be part of an enemy plot to sabotage the nation's morale. Sadly, a military intelligence investigation showed otherwise.

Nevertheless, the MCWR met its goal on schedule and reached strength of 18,000 by 1 June 1944. Then, all recruiting stopped for nearly four months and when it was resumed on 20 September 1944, it was on a very limited basis.

Everyone agreed that the MCWR's recruiting success was directly tied to the Marine Corps' reputation — the toughest, the bravest, the most selective. Women like Inga Frederiksen did not hesitate to accept the challenge of joining the best. When a SPAR recruiter told her she was smart not to join the Marines because they were a lot rougher, Inga knew she had to be a Marine.

Early Training: Holyoke and Hunter

Thanks to the Navy, officer training began when the MCWR was only one month old. Sharing training facilities saved time and precious manpower in getting the women out and on the job. Moreover, Marines benefitted from the Navy's close relationship with a group of prominent women college presidents, deans, and civic leaders who gave sound advice based on years of experience with women's programs. Just as important they offered several prestigious college campuses for WAVE and subsequently, MCWR training.

The Navy's Midshipmen School for women officers, established at Smith College in Northampton, Massachusetts, later branched out to nearby Mount Holyoke College in South Hadley. Enlisted women were trained at Hunter College in New York City, and without question, the distinguished reputations of these two institutions enhanced the public image of the WAVES and the women Marines.

The first group of 71 Marine officer candidates arrived at the U.S. Midshipmen School (Women's Reserve) at Mount Holyoke on 13 March 1943. The women Marines were formed into companies under the command of a male officer, Major E. Hunter Hurst, but, similar to Marine detachments on board ships, the WR unit was part of the WAVES school complement, under final authority of the commanding officer of the Midshipmen School.

Officer candidates joined as privates and after four weeks, if successful, were promoted to officer cadet, earning the right to wear the coveted silver OC pins. At that point women who failed to meet the standards were given two options: transfer to Hunter College to complete basic enlisted training or go home to await eventual discharge. Cadets who completed the eight-week course but were not recommended for a commission were asked to submit their resignations to the Commandant. In time, they were discharged, but permitted to reenlist as privates unless they were over age.

A disappointment shared by members of the first Officer Candidates' Class (OCC) and recruit class was the scarcity of uniforms. Both trained for several weeks in civilian clothes because uniform deliveries were so slow. In fact, the official photo of the first platoon to graduate from boot camp at Hunter College is a masterful bit of innocent deceit because as Audrey L. Bennington tells it, "Only the girls in the first row — and a few in the second row — had skirts on. We in the other rows had jackets, shirts, ties and caps, but — NO skirts. Lord and Taylor was a bit late in getting skirts to you.

Recruits received very precise and clear instructions before leaving home. They were told to bring rain coat and rain hat (no umbrellas), lightweight dresses or suits, plain bathrobe, soft-soled bedroom slippers, easily laundered underwear, play suit or shorts for physical education (no slacks), and comfortable dark brown, laced oxfords because, ". . . experience has proven that drilling tends to enlarge the feet." They were also warned not to leave home without orders, not to arrive before the exact time and date stamped on the orders, and not to forget their ration cards.

During the first four weeks the MCWR curriculum was identical to that of the WAVES, except for drill which was taught by reluctant male drill instructors transferred to Mount Holyoke from the Marine Corps Recruit Depot, Parris Island, South Carolina. Officer candidates studied naval organization and administration, naval personnel, naval history and strategy, naval law and justice, and ships and aircraft. The second phase of training was devoted to Marine Corps subjects taught by male Marines and later, as they, themselves became trained, WR officers. This portion of training was conducted apart from the WAVES and included subjects such as Marine Corps administration and courtesies, map reading, interior guard, safeguarding military information, and physical conditioning.

On 6 April, members of the first officer class received their OC pins and on 4 May history was made as the first women ever became commissioned officers in the Marine Corps. Retired Colonel Julia E. Hamblet, who twice served as a Director of Women Marines, recalled the comical reactions she and other women of the first officers class received: "That first weekend, we were also mistaken for Western Union girls."

The Marine Corps section of the Midshipmen School operated on a two-part overlapping schedule, with a new class arriving each month. The first three classes each received seven-and-a-half weeks of training. In all, 214 women officers completed OCC